When it was her turn to host all her fellow middle school math teachers, her boss and her boss’s boss to observe one of her eighth grade math classes at Evergreen Middle School in Hillsboro last month, teacher Alex Krabiel decided she’d go out on a limb.

They’d come to the class that had started off the school year as one of the toughest she’d ever taught.

“There was a lot of energy in that class,” Krabiel told her colleagues. “It was a lot of me working with admin, of moving schedules. It was a lot of resetting expectations, almost daily.”

But with just a few more weeks left until summer break — and after a school year in which the Evergreen staff went all-in on a strategy centered on student conversations — Krabiel was ready to show off her eighth graders, confident they would come through for her.

Evergreen, which enrolls 700 seventh and eighth graders, nearly 50% of them Hispanic or Latino, is one of Oregon’s “targeted improvement schools.” That means it receives some extra money from the state because one or more of its student demographic groups need to improve their performance in core academic topics.

Hundreds of schools around Oregon share Evergreen’s targeted improvement status. But in the

absence of hard-and-fast state guidance

, the intervention strategies they use to help their students vary widely – and so do the results.

Hillsboro, Oregon’s fourth largest school district, has won past plaudits from both Gov. Tina Kotek and the nonprofit Foundations for a Better Oregon for its use of data to drive its spending decisions.

And amid dismal post-pandemic test scores statewide — and with middle school math newly under a statewide microscope thanks to

an accountability bill under consideration in the legislature this year

— academic pay-off in that realm carries extra importance.

That meant Evergreen Principal Kevin Hertel and his faculty had to figure out how to help the broadest number of students on a tight budget. They were guided by the work of influential Australian education researcher John Hattie, whose career-spanning

meta-analyses

of which factors make the most difference in a classroom rank both teacher quality and student collaboration at or near the top.

Evergreen’s goal, Hertel said, was to put the two together. Teachers met in subject area groups three times this year to design, observe, analyze and plan lessons that would do just that. The ones they designed set students up to work first on their own and then in small groups to solve math and science problems and unpack complicated concepts in English and history. When the small groups have reached consensus – or hit a roadblock — they’re ready to share their conclusions with their classmates.

The strategy — shorthanded as “pair and share” — doesn’t sound immediately revolutionary. But the magic is in the details, Evergreen educators say: How students are set up for small group conversations and how they can learn to advocate for themselves, self-correct mistakes and listen to their peers.

It’s especially key for students in the pandemic generation, who spent formative school years online and got used to texting instead of talking and turning off their cameras while listening to others speak, Hertel said. Over the course of this school year, the Evergreen staff has watched even shy students find their voices in class and seen promising growth for those new to speaking English.

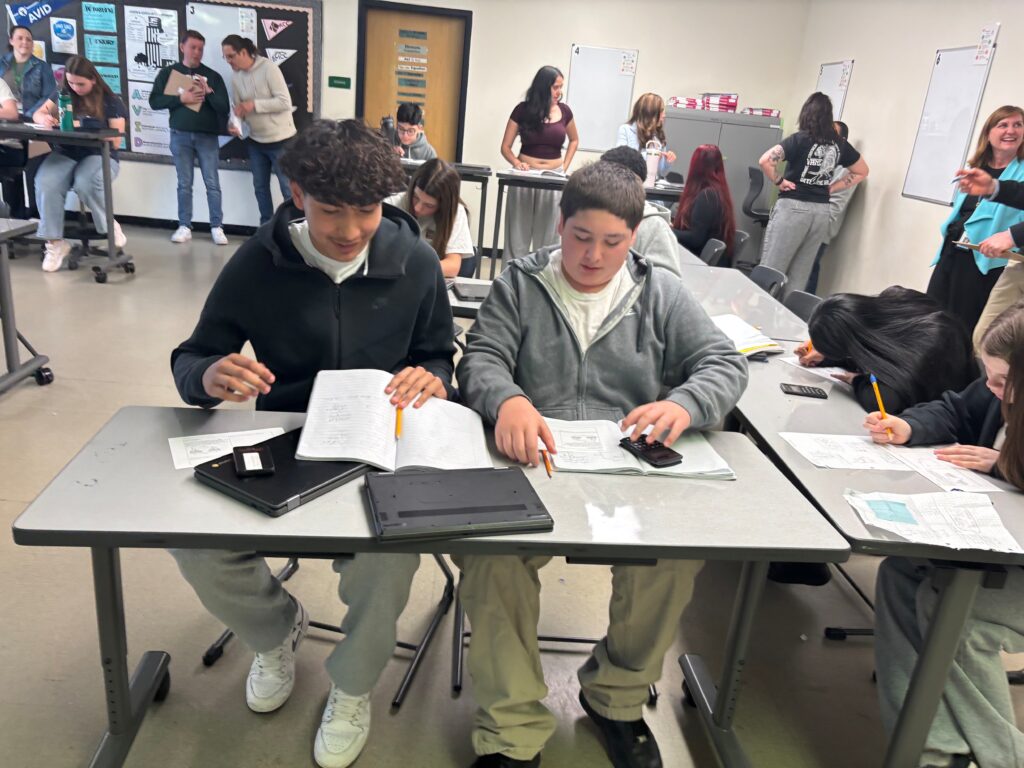

Evergreen Middle School math teacher Alex Krabiel walks her class through a math problem before they try to solve it, then divide into pairs and groups of three to discuss their solution.

Photo by Julia Silverman

By the time half-a-dozen adult observers filed into her classroom, Krabiel and her students were ready to dissect the Pythagorean theorem, otherwise known as how you calculate the length of the third side of a triangle when you know the measurements of only two of its sides. It’s a key foundational concept for geometry, which lies ahead in high school.

Krabiel started off small: a picture of a triangle, one side 18 units long, one side 11 units long, and the third side a mystery. Her students had to decide for themselves: Were they solving for the hypotenuse or the leg? Once they’d made their decision, they consulted their partners, then turned their attention back to the group at large, since Krabiel let the class know in advance that she’d be calling on groups at random to share and defend their answers.

Next up, Krabiel moved to progressively challenging word problems, trying as she went along to scaffold her students, encouraging them to break each problem into manageable chunks. Figure out what you’re solving for, set up the formula, plug in the numbers, simplify, then add or subtract to solve, she suggested.

“What is this problem about?” she asked, as her students picked up their pencils. “What are you being asked to find? What information is important?”

Evergreen Middle School math teacher Alex Krabiel consults with two of her students as they discuss their solutions to a math problem about the Pythagorean Theorem.

Photo by Julia Silverman

At each step, students worked out their answer, consulted with their partners, then waited to see if Krabiel would call on them to share with the group at large.

“The height of the building is 29 feet, which I got because I found the leg of the triangle and added on the height of the fence,” a student named Ryan volunteered when called on, prompting Krabiel to pump her fist in the air.

“Way to explain the answer!” she exulted. “That was above and beyond.”

A student named Colton said he’d noted that he was spending a lot more time this year in teacher-approved conversations with his seatmates and said he thought it allowed him to hear different opinions.

“I struggle sometimes noticing details,” he said. “So this way, it lets me check my work.”

Early results from the schoolwide focus on collaboration, whether student to student, between teachers or between a teacher and their class, are encouraging, Hertel said, particularly in English, where data from regular check-in tests has shown improvements across grade levels from fall to winter. Math growth is coming more slowly, Hertel said, in part because the school adopted a new math curriculum this year and teachers and students alike have been getting used to it.

Hillsboro’s use of real-time testing data to inform instruction — as opposed to relying on state standardized tests that are given in the spring but don’t yield definitive results until children have moved onto the next grade the following fall — is one practice that Kotek has called for all of the state’s schools to adopt in the coming years. She’s also seeking to add growth in eighth grade math skills to the state’s method for rating school districts’ performance, broadening the focus from early literacy and high school graduation rates.

Both before Krabiel demonstrated her eighth grade teaching skills to her colleagues and bosses and immediately afterward, Krabiel sat for a debrief.

Pre-lesson, the group dove into the nitty-gritty.

-

Sentence frames are a proven way to help students write in full sentences by giving them the first few words, and Evergreen students have used them throughout the year. But so close to the end of the year, would requiring students to paste previously used sentence frames in a designated spot in their notebooks help them write answers in a complete sentence without teacher prompting? Or was it more effective to post sentence frames up on a whiteboard or a poster, for everyone to see?

-

How could teachers best pull in students who are still resistant to sharing their math thinking with a partner?

-

Should the 2025-2026 school year kick off with asking students to turn and talk with each other about non-curricular tasks, so that they can get used to the face-time with each other?

After her demonstration lesson, some of the feedback colleagues offered Krabiel prompted her to blink back tears.

“I just stopped taking notes at one point, and I just took it all in,” said seventh grade math teacher Tatiana Ford. “And I was just like, ‘Alex, you are such an amazing teacher.’ And it was really awesome to see.”

Students felt safe enough with the format to screw up, acknowledge it and try again, teacher Lauren Lawson pointed out — a good sign as they head into more academic independence at the high school.

“There were two students near me who were partners, who had started to solve and they both messed up,” she said. “And the fact that both of them were comfortable recognizing their mistakes and saying out loud, ‘Oh wait, I did this and I was supposed to do this,’ was cool to watch.”

Hertel, too, said Krabiel’s class had shown real growth not just in talking to each other, but in listening to each other, too.

“You had a lot of prep work going into that already that I’m not even sure that you’re aware of,” he said. “Just saying, ‘Ok, Partner A, you’re going to ask Partner B this question, and then Partner B is going to respond’ holds kids accountable to listen. And even having multiple kids share out at the end, the whole class could listen and see the examples.”

— Julia Silverman covers K-12 education for The Oregonian/OregonLive. Reach her via email at jsilverman@oregonian.com.

More Stories

To help middle school mathematicians, a surprising prescription: Get them talking in class

To help middle school mathematicians, a surprising prescription: Get them talking in class

To help middle school mathematicians, a surprising prescription: Get them talking in class