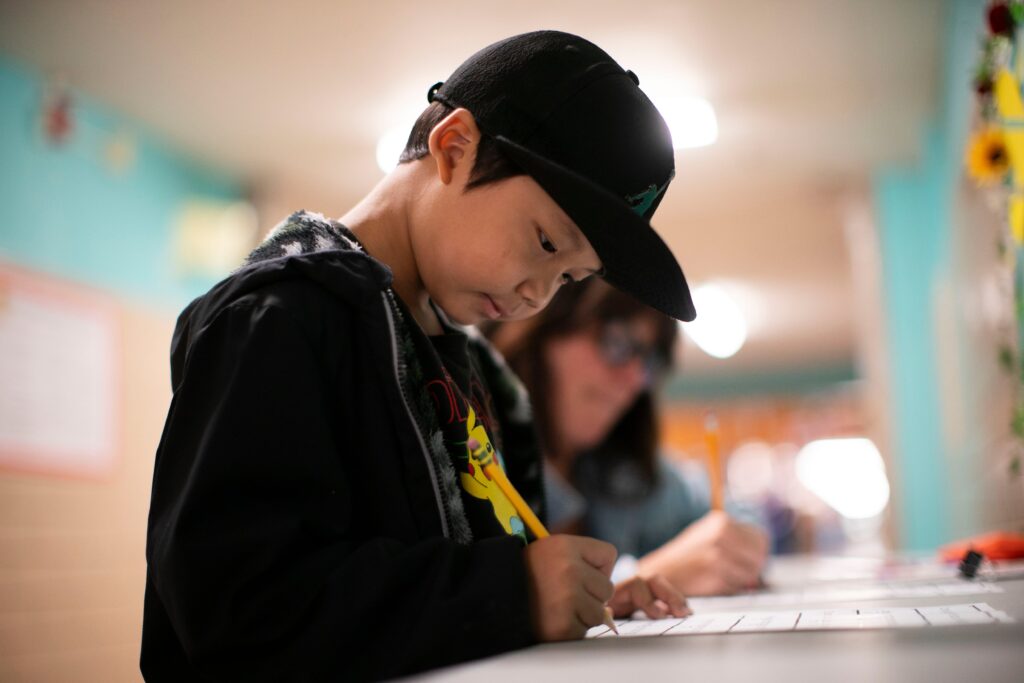

Three mornings a week for the past several months, a Northeast Portland second grader named Jaden has left his classroom for a

30-minute session

focused on taking words apart and putting them back together.

By early June, a week before school was due to let out for summer, Jaden had progressed to reading full sentences with practiced ease, a huge leap forward.

The nearly concluded school year is the first since the pandemic that Oregon’s largest school district went big on

a strategy

that researchers have consistently

pinpointed

as among

the best

to help students who need more help to master grade level reading.

Like Jaden, who attends Scott Elementary, about 12% of Portland Public Schools’ 12,500 students in kindergarten through third grade got help from a reading tutor this year. Fifty elementary and K-8 schools got to take part.

The results are eye-opening.

On average, participating students showed 28% growth on the set of skills they need to read at grade level, said Darcy Soto, the district’s director of academic programs. In kindergarten, that can mean identifying letters and blends, while by third grade it means easily reading and understanding multi-syllable words and entire paragraphs.

Some students showed triple digit improvement in every category, whether decoding simple consonant-vowel-consonant words or unlocking the mystery of the ever-bossy “silent e.”

Buoyed by those results, the district plans to expand tutoring to another five schools next year, funded in part by a $660,000 grant from the district’s parent-generated

foundation

.

The remaining costs, about $520,000 for next year, are slated to be paid by a $93 million renewal of the statewide

Early Literacy Success Initiative

, launched in 2023 to overhaul how the state’s youngest learners are taught to read.

But there’s a catch: the Legislature, grappling with a

bleaker-than-expected revenue picture

and faced with a mound of competing interests, has yet to sign off on spending $93 million on early literacy – and could choose to trim the final amount.

Lawmakers’ decision will shape not only the ability of Portland and other districts to continue their overhaul of early reading instruction but also Gov. Tina Kotek’s educational legacy.

Budget crystal ball

Against the

grim backdrop of the 60%

of Oregon third graders who cannot read proficiently — dramatically increasing the odds that they will struggle for the rest of their school career and drop out before earning a diploma — Kotek threw her weight behind the 2023 effort, which set aside $90 million for early literacy professional development, curriculum, tutoring and summer programs.

Unlike money from the state school fund, which districts may spend however they like, the early literacy money came with strings attached. If school districts wanted to use it to purchase curriculum, for example, their choice had to align with the science of reading, a school of thought backed by decades of brain research that emphasizes phonics and phonemic awareness as key.

Same story for using the funding for training and coaching teachers: Use it for the science of reading, the state said, or no dice. Districts could also use their share for summer learning programs or for reading tutors who would work with children one-on-one or in small groups, meeting multiple times each week.

In her recommended budget for the next two years, Kotek called for reupping the previous funding at the same or slightly higher level. But it’s not yet clear that her recommendation will make it across the finish line, though some literacy advocates have said they are cautiously optimistic. Others are seeking to add

even more oversight

, by requiring that the funding be concentrated in schools where the highest percentage of children struggle to read.

“I think legislators understand the significant need to improve literacy rates in Oregon because we are at the bottom nationally,” said Sarah Pope, executive director of education nonprofit Stand for Children Oregon.

When lawmakers passed the first iteration of the Early Literacy Success Initiative, state education officials cautioned that the impact wouldn’t be immediately apparent. Other states, notably Mississippi, are far ahead of Oregon in adapting a statewide science of reading approach and have seen significant and sustained improvements. But it didn’t happen overnight.

Shifting how reading is taught is a massive undertaking that requires many longtime teachers to drastically rethink their daily classroom routines, And Oregon has not tested students’ reading skills until third grade, meaning that students who’ve had the full benefit of the new literacy approach from kindergarten on won’t sit for such tests until spring 2027.

Tutor Kristen Gallucci works with first graders Mia Nepamuceno, left, and Oromo Aman on consonant-vowel-consonant word recognition. June 5, 2025

Beth Nakamura

Portland’s big bet on tutoring

Still, data like Portland’s suggests the investment is paying off.

Over the past year, Portland directed $838,000 of its share of about $6 million in state early literacy funding to tutoring, after using pandemic relief funds to underwrite

previous, smaller iterations

. Those generally focused on third, fourth and fifth graders who were limited to attending online school in early grades during the pandemic and came back to school buildings far below target levels.

The district had two different models in place this school year, usually during the school day. Some schools, like Scott, were assigned two or three dedicated reading tutors, often parents who were already spending hours volunteering.

They were trained to use tightly-scripted in-house materials designed by district reading specialists to pair with Portland’s existing reading curriculum, so that tutoring could reinforce teachers’ lessons. Doing the tutoring during the school day frees classroom teachers to work with small groups of other students for more individual attention.

In other cases, the district or school contracted with a Portland-based nonprofit called

Reading Results

. Its tutors use a well-regarded curriculum developed by researchers at the University of Florida that complements, but is not directly derived from Portland’s early

literacy curriculum

.

Schools were prioritized for district-funded tutoring based on how many of their students in kindergarten through second grade scored below targets, along with how many full-time staff were already dedicated to reading interventions and the percentage of students in need of help who are from high poverty families, learning to speak English or students of color.

First grader Mia Nepamuceno and her stuffed elephant, whose name is ‘Elephant’ work on reading aloud.

Beth Nakamura

Detailed logs: Wig, fin, tin, bin?

After every session, the army of tutors painstakingly logs information about how each student has performed.

At Scott, that meant charting whether Jaden could pick out which words had short a’s, as in apple, and which ones had long, more drawn-out a’s, like safe, and whether first-grader Mia, who clutched a beloved stuffed elephant named “Elephant” during a recent session, could group words ending in -ig, -it and -in, then read them all aloud in one long blitz, barely pausing for breath. (Spoiler: Yes, she could: “Fit, kit, lit, big, pig, wig, fin, tin, bin!”)

That information, along with quiz results, is turned into neat data visualizations so that their regular teachers can see which skills their students still need to work on.

“I’ve seen so much growth,” said Kristen Gallucci, one of the tutors at Scott, who is also the parent of a third grader and the vice president of the school’s PTA. “I just finished the end-of-year assessments this week and entered all the information in and I was so excited to see how much they’ve learned over the time we spent together.”

At The Oregonian/OregonLive’s request, district officials ran the results of literacy growth among students at four schools across the city who had received tutoring support this year: Marysville Elementary in Southeast Portland, Vernon K-8 School and Scott Elementary in Northeast Portland and Ainsworth Elementary in Southwest Portland.

Among those students, there were a few outliers, like a first grader at Vernon who had gotten over 745 minutes of tutoring support but only showed an 8% overall growth in literacy.

But of the 85 students in the sample, 80 showed double digit growth and about a quarter made triple-digit gains. Some of the best results came from the students at Scott, which receives federal Title I funding due to its concentration of poverty. They included a second grader whose 705 minutes of tutoring over 10 weeks helped them show an astonishing 210% growth, meaning that the students started with beginning first grade level skills and ended fully caught up to her classmates — about two years worth of growth.

A third grader at Scott, who is a native Spanish speaker, got 740 minutes of tutoring and yielded 142% growth. That means the student started the program with the skills of a beginning second grader yet finished by mastering nearly all of the skills required of third graders.

Jaden Aoeun, left, walks down the hallway with Alexa Barron, a reading support educational assistant after a tutoring session.

Beth Nakamura

Scott Principal Tiana Ahmann said she thinks the focused help for younger students will mean even more payoff in the future.

“Targeting K-2 is really helping students get the foundational skills they need,” she said. “That way, by the time they get to grades three, four and five, they won’t need … interventions any more.”

Soto said there’s been growth across the board but the most promising results come from the tutors who use the materials directly tied to Portland’s existing curriculum. Phasing that model districtwide would be prohibitively expensive, though, because Reading Results contracts don’t trigger the same payroll, pension and data collection costs.

Still, Portland Public Schools’ expansion of intensive tutoring next school year could boost students at even more schools.

Alongside Scott, Ainsworth, Atkinson, Beach, Lent, Rigler, and Sitton elementaries will continue to offer the reading tutor model with multiple tutors assigned to their school, joined by James John K-5 and Cesar Chavez K-8 next year — all Spanish dual immersion schools. Another five schools will continue to deploy support from a single reading tutor – including Alameda, Chief Joseph, Glencoe, Rose City Park and Woodstock elementaries – while Arleta K-5 will join their ranks.

The district will pay for Reading Results to work with 30 more schools: Astor, Boise-Eliot/Humboldt, Bridger Creative Science, Bridlemile, Buckman, Capitol Hill, Chapman, Clark, Creston, Duniway, King, Faubion, Grout, Hayhurst, Irvington, Kelly, Laurelhurst, Lee, Maplewood, Markham, Marysville, Peninsula, Rosa Parks, Sabin, Stephenson, Vernon, Vestal, Whitman, Woodmere and Woodlawn.

Another 10 schools have been prioritized to pilot a virtual tutoring program called Amira that’s powered by artificial intelligence and offers support for students all the way through fifth grade. The tool has been

used to great effect

in states including Louisiana, Soto said. Those schools include Abernethy, Beverly Cleary, Forest Park, Lewis, Llewellyn, Richmond, the Metropolitan Learning Center, Rieke, Skyline and Sunnyside schools.

— Julia Silverman covers K-12 education for The Oregonian/OregonLive. Reach her via email at jsilverman@oregonian.com

More Stories

In Portland, intensive reading tutoring delivers eye-opening results, propels some children to grade-level in months

In Portland, intensive reading tutoring delivers eye-opening results, propels some children to grade-level in months

In Portland, intensive reading tutoring delivers eye-opening results, propels some children to grade-level in months